Memory and Resistance: Oyneg Shabes (Joy of the Sabbath)

|

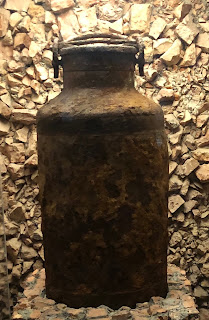

| The milk jug on display at the Ringelblum Historical Institute in Warsaw |

For many Jews, the mitzvah of enjoying the Sabbath (oyneg shabes in yiddish) means eating well, taking a stroll with your family, relaxing, connecting with your children. For Emanual Ringelblum, however, Oyneg Shabes was his secret code for resistance, and for the regular Sabbath meetings in the Warsaw Ghetto of his clandestine group. It’s an incredible story that teaches us a lot about Jewish resistance in general and more specifically resistance to the genocidal intentions of the Nazis. In Warsaw we visited the Emanuel Ringelblum Jewish Historical Institute, which is devoted to telling this story.

It is a story about a specific form of resistance, spiritual resistance. Knowing the likely fate of all those forced into the Ghetto beginning in November 1940, and realizing that memory and how a people will be remembered is a great treasure, Ringelblum and the sixty other community activists working with him asked, “who will tell our history to the world?” “How will be remembered?” “Will we even be remembered in the face of Nazi efforts to wipe out our people, culture and religion?”

They answered these questions and resisted the Nazi plans for erasing Jewish memory, by seeking to build a true history of Ghetto life ... and death. They did this at great risk by systematically organizing an archive of personal testimonies from people in the ghetto about their experience. This included diaries, letters, essays by children, accounts of refugees coming from other areas, poems, official German notices, public announcements, underground newspapers, social/cultural studies, art work, photographs, postcards from Jews outside the Ghetto pleading for help as they faced deportation, interviews and much more. Despite their bleak situation, they looked to the future, and to future historians who would need this source of historically relevant material, documentation and testimonies to tell the Jews’ own stories and to seek some measure of justice for them.

This archive eventually totaled 30,000 sheets. But how could they preserve it for future generations, knowing both the impossibility of smuggling it out and the fate of the Ghetto?

They chose to bury the archive, in three separate basement locations within the Ghetto. Ten tin boxes in one location; two large milk cans in another. Only a few members of Oyneg knew where the material was buried, and only three survived. Despite the fact that the Ghetto was reduced to rubble, miraculously in 1946 the cache of boxes was retrieved, and in 1950 the milk crates. With painstaking restoration work over the following years, the archives were mostly restored, and Jewish memory survived.

|

| How could the metal boxes and milk tins be found underneath all this rubble? Hint: Surviving members of Oyneg Shabes used the still standing tower as a guide. |

|

| Unearthing the metal boxes in 1946 |

|

| Memorial marking the place at 68 Nowolipki Street in the former Warsaw Ghetto where the archive was found and unearthed. |

|

| The Ringelblum Archive compiled filled many volumes. |

Comments

Post a Comment