Memory Keepers

|

| One of the panels containing a number with the Feuer surname |

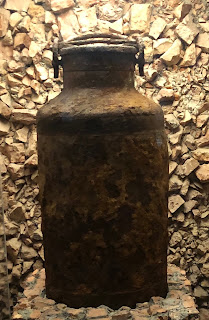

There is a memorial in the city of Nowy Sącz (in southern Poland, not far from Kraków) that has two stories to tell. The first is about the 12,000 Jews from Nowy Sącz and surrounding shtetls murdered by the Nazis in 1942. The full telling of this story took place eighty years later this past August when city unveiled a powerful memorial to these murdered citizens. Almost 100 descendants of the victims, from throughout the world, attended the ceremony. The special significance of this remembrance is that it contains every name inscribed in long columns, and each was read out during the ceremony. The town square where the memorial is located, across from the old synagogue, was renamed Square of Remembrance for the Victims of the Holocaust. (There are a number of Feuers represented on the victim list, but I am not aware of any specific kinship to any of them.) Gathering all the names was no small task, taking a team of 20 volunteers in Poland and abroad over a year.

The second story told through this memorial, and its additional significance, is that it was conceived and produced by a Polish group, “People, Not Numbers.” It is the group’s fifth, and most ambitious memorial to victims of the Holocaust. It is, they say, a “symbolic burial for victims who were deprived of humanity [and who] were also deprived of the right to a dignified burial. From now on, their names are etched in stone and have a place where they can be mentioned. We believe that this way we do the right thing and stop the monstrous spiral of evil that triumphs with every passing day of oblivion.”

Dariusz Popiela, founder and director of People, Not Numbers, is a Polish athlete, a world-class kayaker born in Nowy Sącz. He grew up knowing nothing about the Jews who lived in Nowy Sącz for centuries, thriving there, making up one-third of the town’s population and developing a renowned center of Hasidism.

When he learned what he had never known he was determined to change that, not only for himself but for all other Poles. In doing so, and this is the special additional significance to us of this memorial, he is replicating what many other Polish Christians have been doing for the last three decades – rescuing Jewish memory. (Watch an interview with Popiela - https://neshomaproject.org/

“Today, all over Poland there are people who, in big ways and small, through institutions and on a grassroots level, are remembering Jews,” writes Leora Tec on her website (neshomaproject.org) which seeks to embrace and interview many of these people. [Leora was our Polish teacher and is herself the daughter of Holocaust survivors, hidden by Poles during the war. Her mother, coincidentally, is from Lublin, where my mother’s family is also from.]

Both in our preparation for this journey and throughout our time here we have experienced the truth of Leora’s words about Polish memory keepers in a myriad of ways. But it is a view that is contentious. Others have diminished the work of such people.

“Places around the world now largely devoid of Jews have come to think fondly of the dead Jews who once shared their streets,” writes Dara Horn in a 10/4/21 NY Times opinion piece. “An entire industry has emerged to encourage tourism to these now historical sites. The locals in such places rarely minded when living Jews were either massacred or driven out. But now they pine for the dead Jews, lovingly restoring their synagogues and cemeteries …. Some [such heritage sites] are maintained by sincere and learned people, with deep research and profound courage. I wish that were the norm. ... Many Jewish travelers to such sites feel a discomfort they can barely name. I’ve felt it too, every time. I’ve walked through places where Jews lived for hundreds or even thousands of years, people who share so many of the foundations of my own life — the language and books I cherish, the ideas that nourish me, the rhythms of my weeks and years — and I have felt the silence close in. I don’t mean the dead Jews’ silence, but my own. I know how I am supposed to feel: solemn, calmly contemplative, and perhaps also grateful to whoever so kindly restored this synagogue or renamed this street. I stifle my disquiet, telling myself it is merely sorrow, burying it so deep that I no longer recognize what it really is: rage.”

Horn is too harsh we think, but her point is worth bearing in mind. For us, however, and I think many others, it is nothing short of miraculous to be able to come here, and thanks to these very sincere and learned Polish memory keepers to be able to experience in profound and meaningful ways what was. But more than this. It is not only for us. It is also for all those Poles, growing up now or having grown up already without any of this historical knowledge or feeling, but now being confronted with and learning about this history. There is no shortage of young people in class outings visiting these sites; or groups of their elders visiting from all over Poland. I am moved, for example, in Nowy Sącz when I observe an older Polish woman reading the explanatory plaques about what happened 80 years ago in her town and what Jewish history there in Nowy Sącz was all about.

|

| The Nowy Sącz Memorial is below ground, with panels containing all the names |

|

| The dedication ceremony |

|

| A Polish woman reading the descriptive plaques about the history of Nowy Sącz Jews |

|

| One wall of panels. |

|

| The Nowy Sącz synagogue right across from the memorial. |

|

| Hasidic Rebbe Chaim Halberstam (1793-1876), founder of the Sanz Hasidic dynasty and one of the leaders of East European Jewry during his life. |

Comments

Post a Comment