Przecław

|

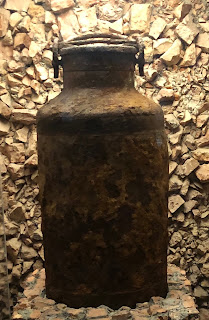

| Portion of Pshetzlov Market Square, 1912 (my father was 1 year-old) |

We’ve visited 6 communities where shtetls existed before the Holocaust wiped out

everything, and are staying in Kazimierz, the old Jewish part of Krakow, itself virtually also a

former shtetl (shtetl is the Yiddish word for town; plural, shtetlekh). One of the towns we visit is

Przecław where my father was raised until leaving for America at the age of 18 in 1929.

Those we visited are a tiny sample of the close to 2,000 that existed in the former Polish

Commonwealth (including Lithuania, Belarus and parts of Ukraine). The shtetls (small towns

with a significant Jewish community living along with Catholic Poles) were ubiquitous and

formed a closely connected and interwoven web of Jewishness in Poland. As we travel the

countryside, it is amazing that every 10 or so miles another shtetl existed, that they each

represented or embodied a vibrant Jewish life, religion, and culture, and that they were often

connected to each other, with high rates of intermarriage and sharing various communal

services.

It is sobering, saddening, and maddening to ponder the destruction, but at the same time

uplifting to remember, learn about and in a small way experience all that was here. We are

blessed to be able to be here and have this experience. Our teacher and guide, Tomasz

Cebulski, captured some of this post-Holocaust possibility: “Now only the towns, streets and

houses remain as silent witnesses of that life. There are many places all over former Galicia,

where we can still catch a glimpse of the historic greatness of a shtetl. A synagogue at the

town's limits, an old marketplace with wooden houses and a bit neglected cemetery with

matzevot [Jewish tombstones] create all together a characteristic landscape for many towns in

this region.”

Przecław, my father’s shtetl, was smaller than most: only about 200 Jews in a town with less

than 1,000 people overall in 1900; compare this, for example, to nearby Kolbuszowa (where my

bubbe was born) with 2,000 Jews or two-thirds of total population. Still Przecław embodied all

the features of a shtetl: a small synagogue; mikvah, Jewish cemetery (totally destroyed by the

Nazis, then used as a landfill or dump), beit midrash [place for torah study], cheder (informal

religious school for boys), a rabbinic judge/teacher, market square with mostly small wooden

Jewish-owned or rented houses and shops around it, weekly market days (Przecław was known

for horse and cattle trading), ritual slaughterhouse, an inn leased from the noble that owned

the town, agricultural fields around it, a kehillah or community council; Hebrew as the language

of prayer, Yiddish as the language of the street.

Of course, all this is gone, including any Jewish archival records in the town. We visited the

town clerk, hoping that perhaps some records from my family might be there, but no luck.

None. These records were destroyed by the Nazis as they sought to erase any trace of the

Jewish people from history. While the shtetl is gone, here as elsewhere a thriving market

square with its shops along the perimeter allows us to imagine how it used to be.

Other shtetls we visited are different; in these more memories of shtetl life have been

restored. Most of these cases of restoration involve synagogues and cemeteries. In Kolbuszowa,

for example, with its unique town coat of arms showing Jews and Christians in a handshake of

unity, the former synagogue was restored and is now used as a town cultural center, but with

its shtetl history amply recognized. Similarly, the Jewish Cemetery (containing the Ohel

[structure built around a grave and marking prominence] of Hasidic Rabbi Teitelbaum) was

restored in the 1980s. In Chmielnik (founded 1565; 8,000 Jews or 80% of total in 1901), the

synagogue was restored and transformed into a magnificent Shtetl Museum

(http://swietokrzyskisztetl.pl/asp/en_start.asp?typ=23&submenu=169&menu=169#strona).

The same in Dabrowa Tarnowska (http://www.oskdabrowa.pl/). In all these cases, care and

restoration of the synagogues was transferred from Polish Jewish community authority to the

local community, where local, national or European Community public funds were used for

restoration.

Jews were living in Przecław beginning in the 16 th century, more came after and shtetl life

developed there from then. While shtetl life was vibrant and, in many ways, heavenly for Jews,

not all was perfect over the years. The political economy was far from idyllic. The region, known

as Galicia, when it was under Austria-Hungarian rule in the 19 th /early 20 th century, was

impoverished. The extension of the railroad opened up Galicia to outside

economy/trade/manufactured goods, decimating local Jewish small traders and artisans. And

especially after nationalism took hold and political antisemitism grew in the latter part of the

19 th century, anti-Jewish pogroms engulfed the region, in 1898 and 1919.

If you are interested in a general article about shtetls -

https://yivoencyclopedia.org/article.aspx/shtetl

|

| Ceiling and portion of wall of restored synagogue in Dabrowa Tarnowska (no Jews living there) |

| ||

Inside of restored Chmielnik synagogue, now a museum of Jewish life

|

|

| Some of the matzevot that have been recovered for eventual restoration in Szydłów cemetery. |

|

| Plaque commemorating the Kolbuszowa Synagogue restoration. Note the official town Coat of Arms linking town Jews and Christians, and created following 1919 pogrom there. |

Kolbuszowa Cemetery with over 200 matzevot.

There is also in the cemetery about a thousand Jews who were shot by the Nazis. On the 10th anniversary of the murder, a monument was erected over their grave with the inscription in Polish, "Polish citizens of Jewish nationality, victims of the fascist terror of 1943."

Comments

Post a Comment