Fejga Estera Hochberger

On June 6, 1928, the 16-year old Fejga Estera Hochberger boarded the SS France in Le Havre, France for the trans-Atlantic journey to America. She was with her mother, Szajndla, and her brothers Pejsach and Szloma. The journey to New York had taken the family from their flat at 81 Lubartowska St. in Lublin, a city in Poland’s east. It was a journey her father, Chaim, had taken some seven years earlier. With their Immigration Visas issued April 16, they took the train from Lublin to Warsaw, then on to Gdańsk where they took a boat to Le Havre. She arrived in NY Harbor and a new life. No longer a Lubliner, she never looked back, rarely spoke of Poland, and never returned.

But what if Fejga had never boarded that vessel, and remained in Lublin instead? Visiting Lublin, we seek to trace her fate.

Staying in Lublin after 1928, she and the family would have experienced a decade of economic struggles during the depression and political struggles in the 1930s with a growing nationalist and anti-Semitic populist movement that wanted Jews out. Still she would have been enthralled with Jewish cultural dynamism and a large Jewish community numbering around 40,000 or one-third of Lublin. Seven synagogues functioned, along with several dozen prayer houses and numerous social, cultural, educational, and recreational institutions. Yiddish newspapers flourished. There was a lively Jewish political culture with a number of active socialist, Zionist and religious parties. In 1930, just down the block from where Fejga probably would have continued to live, a large Yeshivah opened, the Chachmei Lublin Yeshiva, one of the grandest in the world at the time.

But this life would change irrevocably on September 1, 1939. On that day Germany invaded, and Nazi planes began nightly attacks over Lublin, followed by ground forces two weeks later. On the 18th, it was over. Six hundred were killed and many homes destroyed. How terrifying, but worse was to come. The Nazis were in control now. How much worse it would become, perhaps they would not be aware.

Immediately the Germans began to transform and dominate the city, oppressing all, but Jews especially. Armbands with the Star of David worn on the right sleeve began to be required, and then 500 families were forced from their homes – with 10 minutes notice - because the powerful, vicious, and anti-Semitic SS head, Odilo Globocnik, did not want them close to his staff headquarters. Roundups and forced labor. Numerous work camps established in the city. Houses destroyed and looted. All the synagogues and houses of prayer closed.

On March 24, 1941, conditions worsened when 34,000 Jews, most of the Lublin population, were ordered into a specifically Jewish ghetto, barbed wire fence put up and a few entrance/exit gates established. The Hochberger apartment at 81 Lubartowska was within the ghetto district so they wouldn’t have had to relocate. But Jews forced into the ghetto had their property confiscated, and most likely some of these would have been family or friends who would have begun to double up in the Hochberger apartment. So, conditions worsened even more, including food scarcity.

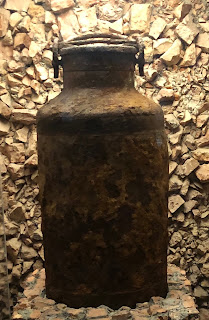

Genocide would follow. Beginning on March 17 1942, a minimum of 1,400 Jews each night were rounded up from the Lublin ghetto, assembled at the Synagogue, then force-marched 4.5km (2.8 miles) through darkened streets to the Umschlagplatz (Nazi euphemism for collection point or holding area where Jews were assembled for deportation usually to death camps), an old slaughterhouse, and from there loaded onto cattle cars and taken to Bełżec, about 2 hours away.

When would it have been my mother’s turn; my grandmother; my uncles? Or would they have been just shot dead during the roundups, whether in the streets, their apartment or in a hideout? Or if they lagged or fell during the forced march to the Umschlagplatz?

We traced the steps at Bełżec too. Parking at what is now the memorial site, we crossed the train tracks where people were viciously pushed off, and entered the site as they would have, but without the horror and fear of the unknown. And without being stripped as they were and immediately marched down the long path to the gas chamber. Our visit to Bełżec was the most difficult and somber moments of our entire trip.

The deportations from the ghetto continued until April 11. Only about 4,000 Jews remained alive. These were sent to a new smaller ghetto in a suburb of Lublin (Majdan Tatarski). Perhaps Fajga, ever resourceful, would have been among them. But soon they were hauled to Majdanek concentration camp, on the edge of Lublin and murdered there later in the year. Meanwhile Jewish forced labor was used to demolish all the buildings in the Jewish quarter. The huge Maharshal Synagogue, originally built beginning in 1567 and the pride and joy of Jewish Lubliners, was blown up. The Jewish presence in Lublin had been almost totally eradicated.

In the end, of the over 40,000 Lublin Jews only around 200 survived in occupied Poland, hidden by Poles or with falsified documents. Others – perhaps 1,000 - were able to escape to the Soviet Union or elsewhere. But Jewish Lublin was no more.

“Lublin, my holy Jewish city,….. city of joyous Jewish holidays.... Lublin, my holy city of young boys and girls thirsting for education.... Holy city of mine.... Who will raise you up again and rebuild you, my holy city, now that you’ve been razed to your foundations, are one frightful gravestone?” (Jacob Glatstein, “Lublin, My Holy City,” full text below)

Mom, we are glad you left when you did and lived to be 103. And also glad that grandma, Uncle Phil and Uncle Sam left with you.

Jacob Glatstein': “Lublin, My Holy City”

Lublin, my holy Jewish city, city of great Jewish poverty and joyous Jewish holidays. Your Jewish street smelled of whole-wheat bread, sour pickles, incense, herring, and Jewish faith. The Hasidic synagogue, the Maharam synagogue and the Maharshal synagogue, the workers’ little houses and little synagogues all gave an air of holiness to the inter-Sabbath periods of everyday commerce, so to speak. The flour-covered bearers who stood and waited for a tip, and meanwhile slipped into the Hassidic synagogue and enjoyed the congregation’s chant – the light, silky, satiny voices of the young men.

Lublin, my holy city, city of awakened class struggle. Your tailor-boys and cobbler-boys, your apprentices and servants, rose up to introduce justice, equality, and brotherhood for all “comrades and citizens.” A holy flame purified their eyes when they went joyfully to the tribunal, singing revolutionary songs along the way.Lublin, my holy city of young boys and girls thirsting for education; of the first lilac aroma of early Hebrew and the deliciousness of proud Yiddish; of the modern Hebrew schools, the Hazamir choral society, and the professional unions; of our joint yearning for Odessa and Warsaw, where we made a fuss over Bialik, Frishman, Mendele, Peretz, Sholem Aleichem, and Reisen; my city of enraptured painters, poets, and violinists.

Lublin, my holy city, with the old-old and new-old cemeteries, with the mausoleums of Hssidic rabbis, graves that one might not approach except in times of great trouble, for their ground fairly burned with holiness.

Holy city of mine, you asked this honor for yourself: that when they would burn and roast a million-and-a-half Jews they should do it in the shadow of your nearly thousand-year history of Jewishness. This holy cemetery you wanted for yourself, so that all your holy tombs should together become one holy tomb for a great tsaddik – the Jewish people. I take off my shoes when I come to the Majdanek woods. The ground is Holy of Holies, for the Jewish people lies resting there in the shadow of hundreds of pious generations.

Who will raise you up again and rebuild you, my holy city, now that you’ve been razed to your foundations and are one frightful gravestone? They are hammering shingles and laying roofs, they are repairing and tidying up the old, disgusting world. But my holy city, the city of my world, will never be rebuilt.

|

| Maharshal Synagogue destroyed by the Nazis along with the entire old Jewish quarter. |

|

| Ghetto enclosed with barbed wire and just a few entrances in or out |

|

| Memorializing the death march at Bełżec into the gas chamber. Bełżec itself was quickly destroyed by the Nazis when they were no longer using it. |

|

| Bełżec Plaque |

.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment