Kazimierz

|

| Mordechaj Gebirtig |

|

| Remuh Synagogue today, where services are held; one of 7 standing synagogues in Kazimierz. |

I start with Mordechaj Gebirtig. I am drawn to Gebirtig, whom I knew nothing about until our trip. He was a bard for the workers and the poor, with songs about Jewish struggles, family life and suffering. One of the greatest Yiddish songwriters during the 1920s and 30s, he was sometimes likened to Bob Dylan. Born to a poor family in Krakow in 1877, he made his living and supported his family as a carpenter. His most famous song, which became “an anthem of the ghettos” was “It is Burning” (S’brent undzer sztetł, brent), commemorating a 1930s pogrom in Przytyk where three people were killed and several dozen injured. In 1942, along with other Kazimierz Jews he was forced into the ghetto in the Podgórze district, and then murdered in the street. His wife and three daughters died in the Bełżec death camp. (More on Gebirtig: http://www.zchor.org/fater/

Gebirtig’s murder in 1942 took place during the 1940-43 Nazi campaign to depopulate Kazimierz, the Jewish community of Krakow, and destroy its Jewish culture. They didn’t succeed. The evidence for that assertion may be weak – as the murder of Gebirtig and 60,000 others can attest to - but attending Kol Nidre services at Remuh Synagogue in Kazimierz – as Jews have done for 500 years – convinces me of its reality – and brought back fond memories of my father who could have easily been one of those also attending the service (though he’s unlikely to actually ever been here). (The service also convinces Carol, seated in the back women’s section and unable to see anything of the service, of the reality of historic Jewish inequalities).

Remuh is one of 7 magnificent synagogues all beautifully restored and maintained in Kazimierz. (They survived the Nazi’s because they were used as stables and storage places for grain and looted furniture.) It’s the only one with regular services (though small, with only 60 seats in the men's section). The Jewish population has grown since the Holocaust but is still small, perhaps several hundred. Remuh holds a special place in Judaism and Jewish culture because of its connection to Rabbi Moshe Ben Israel Isserles. The synagogue was built for him around 1558 by his rich father, a merchant and banker for the king. Isserles was an outstanding Talmudic scholar, founder of the Kraków yeshiva (one of the most important centers of Jewish learning in the world at the time) and author of an authoritative text on Ashkenazi Jewish practice. He was known as Remuh. It is partly because of his text that most Jews in the world today with East European roots are inheritors of the cultural practices that started here in Kazimierz. The synagogue is small but magnificent. At the eastern wall, there is an Aron HaKodesh carved in stone, dating back to the second half of the 16th century. It is crowned with a rectangular plate with Decalogue Tablets, placed on a pedestal with a verse in Hebrew. At the center of the main hall, there is a reconstruction of the bimah surrounded with an iron-forged lattice. Next to the synagogue, there is a Jewish cemetery established in the mid-16th century, one of the oldest in Europe and where Moses Isserles is buried, along with many other Jews, including a number of Jewish luminaries.

Remuh notwithstanding, a communal tragedy did happen here.

A Jewish presence in Krakow goes back over 600 years to medieval times. Ashkenazi culture developed here alongside Polish Catholic culture, and both are uniquely preserved today in the mostly intact street layout, market squares and incredible architecture. (Krakow was not bombed during WW II, unlike Warsaw, largely because it was inhabited by the Nazi military regime as its headquarters. Hans Frank, Nazi Governor General installed himself at Wawel Castle where he remained head of the government in the occupied territories until the end of the war.) Nothing perhaps can personify this intertwining of cultures better than our apartment in Kazimierz at the intersection of Bożego Ciała (“Body of God” street running up to the Corpus Christi Basilica church founded in 1335) and Meiselsa street (named after the mid-19th century chief Rabbi and active Polish nationalist Dov Ber Meisels). Walking in the early morning through the streets of Kazimierz to get my coffee and pastry from the Polish bakery nearby, I can almost feel myself as being back in time in Jewish Kazimierz (ok, there wasn’t a Polish bakery here then). It is a powerful feeling. Yes, for Jews this was still diaspora, but it was also authentically and intimately Jewish through and through, like the shtetls.

Kazimierz, as the Jewish district, came about in 1492 when Jews were removed out of Krakow to nearby Kazimierz by the King after tension with Christian merchants. It flourished until the 1930s. Then, on September 1, 1939, the Germans invaded. On March 3, 1941 they ordered all Jews out of Kazimierz and into a small ghetto in Podgórze across the river. The monument at the square and our discussions with Tomasz helped us to understand a little of what it might have been like. The people did not realize that the ghetto would continue for two years and many, like Gebirtig, would not survive till its end. Gradually conditions worsened. Suddenly, without warning, on May 29, 1942 German soldiers surrounded the ghetto and ordered any without special permits to assemble in the main square (today, Ghetto Heroes Square), where they were transferred to the railway station, herded into cattle cars, and taken to the Bełżec death camp, in the far east of occupied Poland. Many of the others were sent eventually to three forced-labor camps established for Jews in Krakow (including the largest, Płaszów, whose site we also visit). In October, another round up and mass deportation to Bełżec took place, except for a group of children and the sick who were murdered inside Płaszów. In March 1943, the bloodiest day occurred with more than 1,000 murdered, and the 2-3,000 survivors sent to Auschwitz.

Despite the odds, there were also many acts of physical resistance with the Jewish Fighting Organization (ŻOB) carrying out numerous attacks and acts of sabotage, mostly outside the ghetto. But to no avail.

This tragic story was replicated in the same time period in many Galitzian shtetls. Ghettos were established, the Jews forced into them, then after a while many were sent to forced labor camps, and then the others deported to Bełżec, often by foot. Those unlikely to make the forced march, including the elderly and children, were then murdered in the cemetery or some other secluded spot. Others were murdered in the ghettos. Some of my family members, who did not leave with my father, his siblings and parents, were forced into the labor camps and/or murdered, mostly in Żabno.

I Had a Home, Mordechaj Gebirtig

In the corner of poverty I had a home, once upon a time

A private haven, a place in the world that was my very own

Like a tree connected to a root, I felt a part of it

I thought I will never leave

I had a home like any other man

One room, a kitchen – my whole little world

Together with friends – the most precious gift of all

I sang, I lived as I wished

Then came the enemy who destroyed my world

The meaning of my life stomped to the ground by his boots

He had hatred in his heart and Black Death was reflected in his eyes

My world, my home – defenseless against him

Like a bird who lost his nest carrying fear on his wings,

I walked my wife, my children into the storm of tears

Banned from paradise, I walk into an alien world

Not knowing what sin have I committed

In the corner of poverty I had a home, once upon a time

The smoke is fading, the criminals scornful laughter echoes in the air

There is no choice now; I have to walk among the mockery, cursing and sneers

Though I feel that even God does not know where (I am going)

Our Town is Burning!

It’s burning! Brothers, it’s burning!

Oh, our poor town, alas, is burning!

Angry winds with rage are tearing, smashing, blowing higher still the wild flames—all around now burns!

And you stand there looking on with folded arms, and you stand there looking on—our town is burning!

It’s burning! Brothers, it’s burning! Oh, our poor town, alas, is burning!

The tongues of flame have already swallowed the whole town and the angry winds are roaring—the whole town is burning!

And you stand there looking on with folded arms, and you stand there looking on—our town is burning!

It’s burning! Brothers, it’s burning!

God forbid, the moment may be coming when our city together with us will be gone in ash and flames, as after a battle—only empty, blank walls!

And you stand there looking on with folded arms, and you stand there looking on—our town is burning!

It’s burning! Brothers, it’s burning!

Help depends only on you: if the town is dear to you, take the buckets, put out the fire.

Put it out with your own blood—show that you can do it!

Don’t stand there, brothers, with folded arms! Don’t stand there, brothers, put out the fire—our town is burning…

|

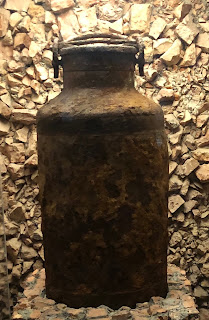

| Cemetery memorial wall - erected after the war and one of the first memorials to the Holocaust; made up of matzevot - Jewish tombstones. |

|

| Ghetto Heroes Square memorial monument; 37 empty oversize chairs symbolizing the items left behind in the square before their owners, the Jewish victims, embarked on their final journey. |

|

| Remuh Synagogue - Aron Hakodesh |

|

| Portion of interior ceiling - Remuh |

|

| Memorial to the victims of the Plaszów labor and concentration camp. The annual march of remembrance ends here. |

Comments

Post a Comment